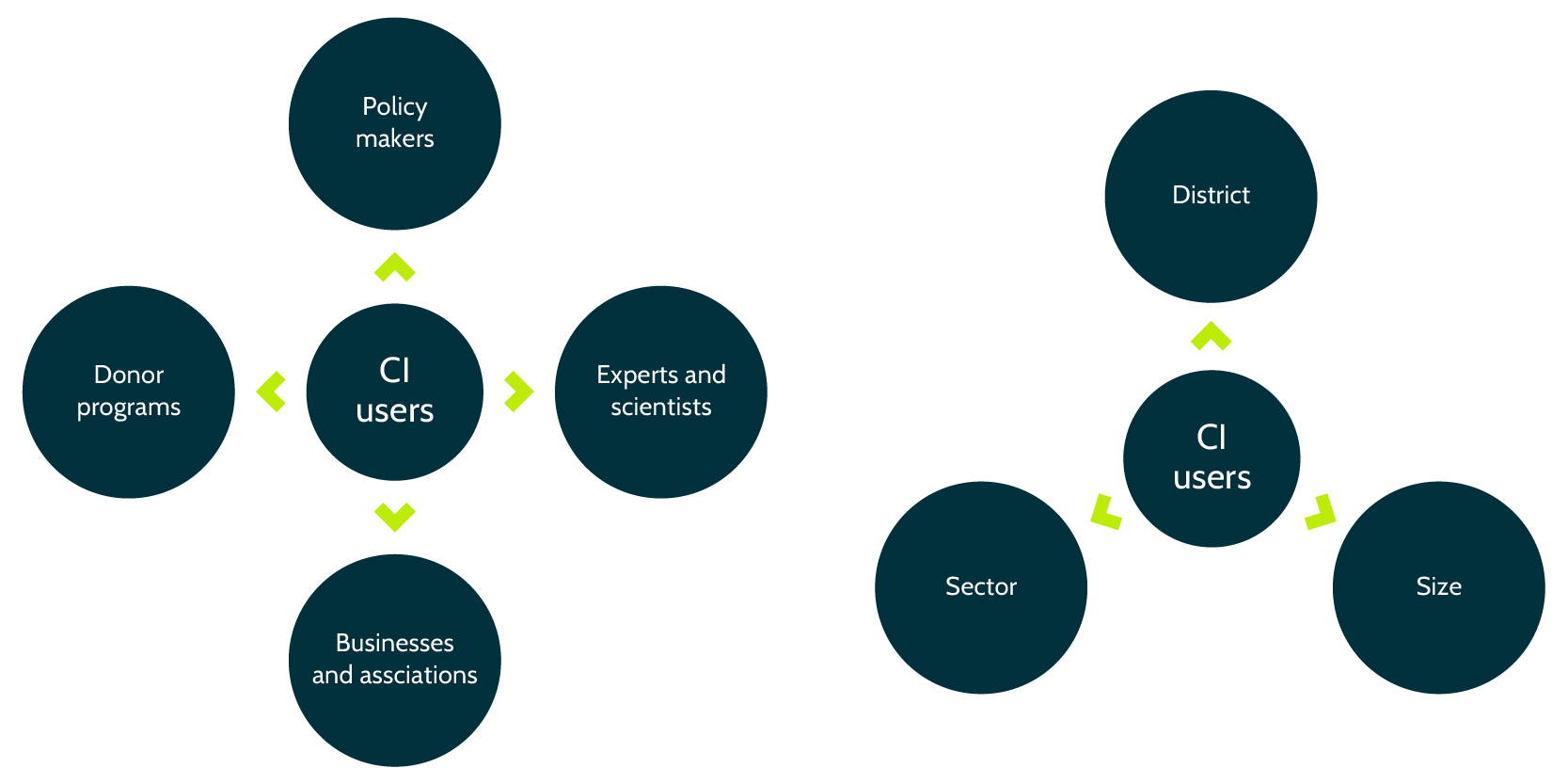

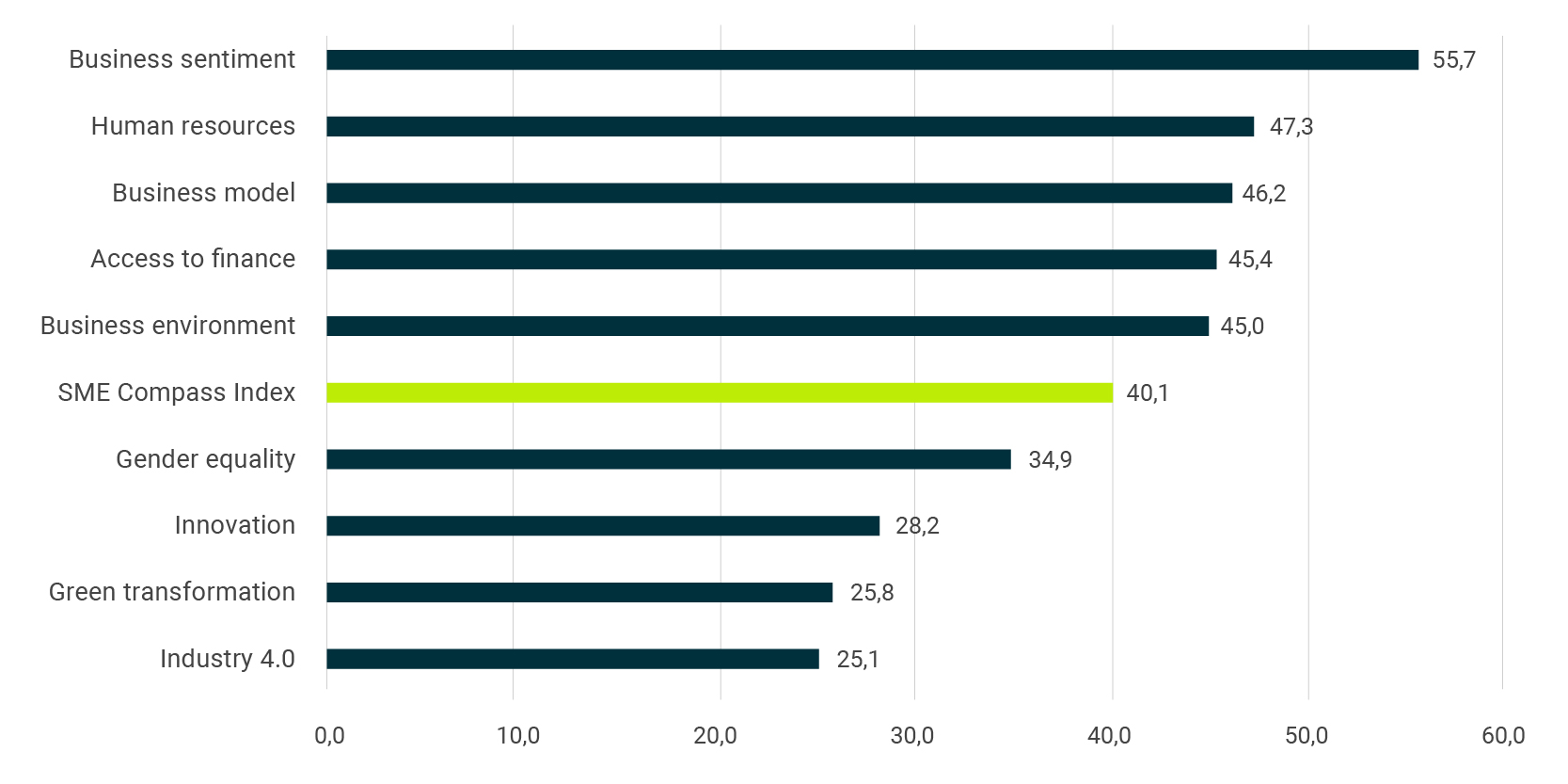

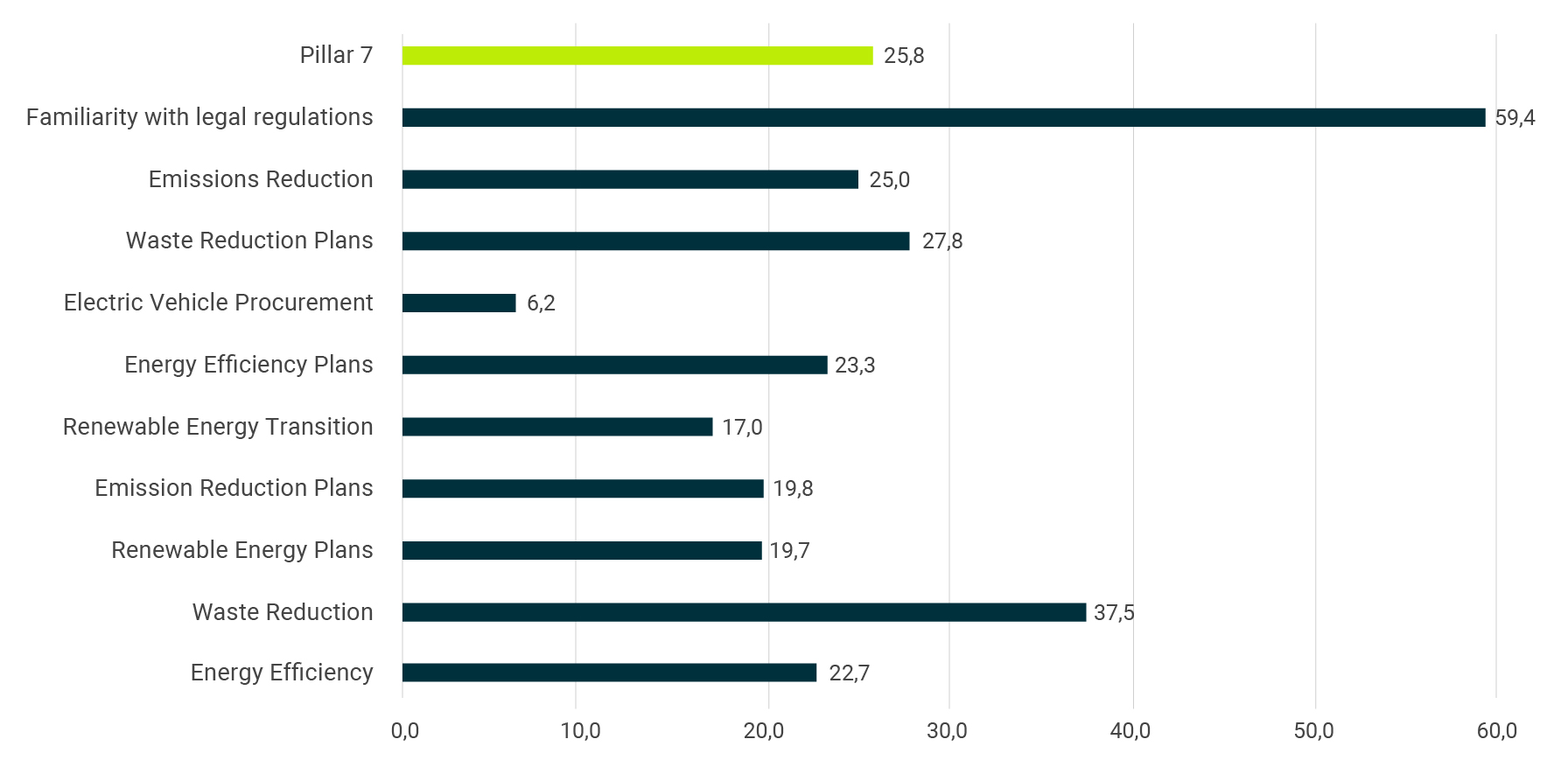

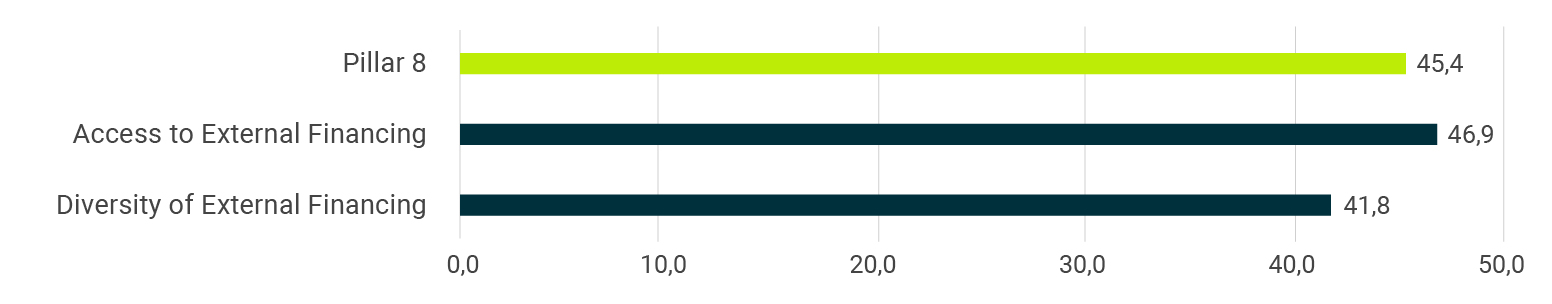

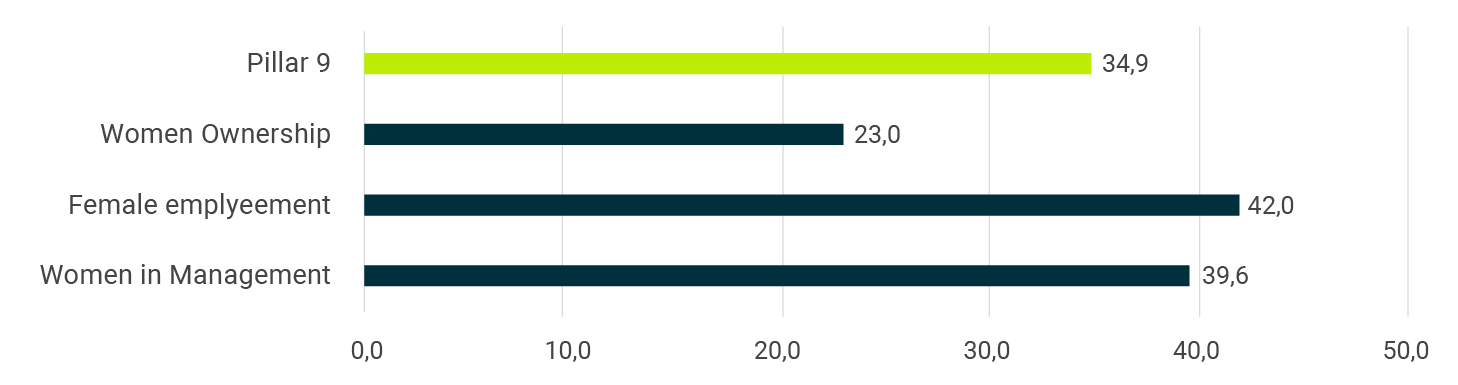

The SME Compass Index (CI) is a composite index that aims to assess the overall competitiveness of the Serbian SME sector. Composite indices are widely recognized as useful tools for analyzing public policies and communicating with the public. They provide a way to summarize complex topics and trends across different fields, making them easier to interpret and compare. The CI combines 75 indicators across 11 sectors, various company sizes, and 25 administrative districts of Serbia. It serves as a comprehensive measure of competitiveness and innovation in the Serbian economy, addressing the shortcomings of previous indices. The index consists of nine pillars, including business sentiment and performance, business environment, human resources, business model, digitalization and industry 4.0, innovation, green transformation, access to finance, and gender equality.

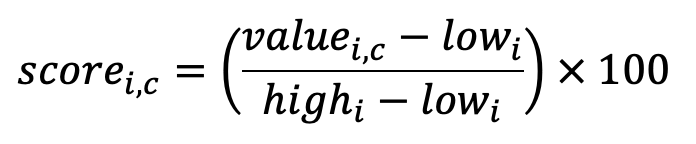

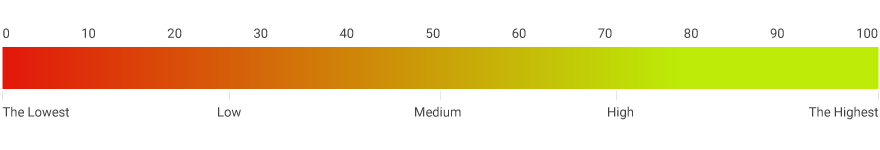

The CI offers valuable insights into the areas where Serbian SMEs are excelling or lagging global trends. This information can guide policymakers, development projects, initiatives, and the monitoring of national strategic documents. The index is accessible through an interactive web portal, providing convenient access to all the necessary information in one place. While composite indices offer advantages such as summarizing multidimensional influences and facilitating communication, their construction and interpretation require transparency to avoid misleading conclusions. Additionally, the choice of indicators and weights can be subjective and contentious. Nevertheless, the CI serves as a valuable tool for initiating discussions, stimulating public interest, and supporting evidence-based decision-making in the Serbian SME sector. All CI indicator scores are standardized between 0 and 100.

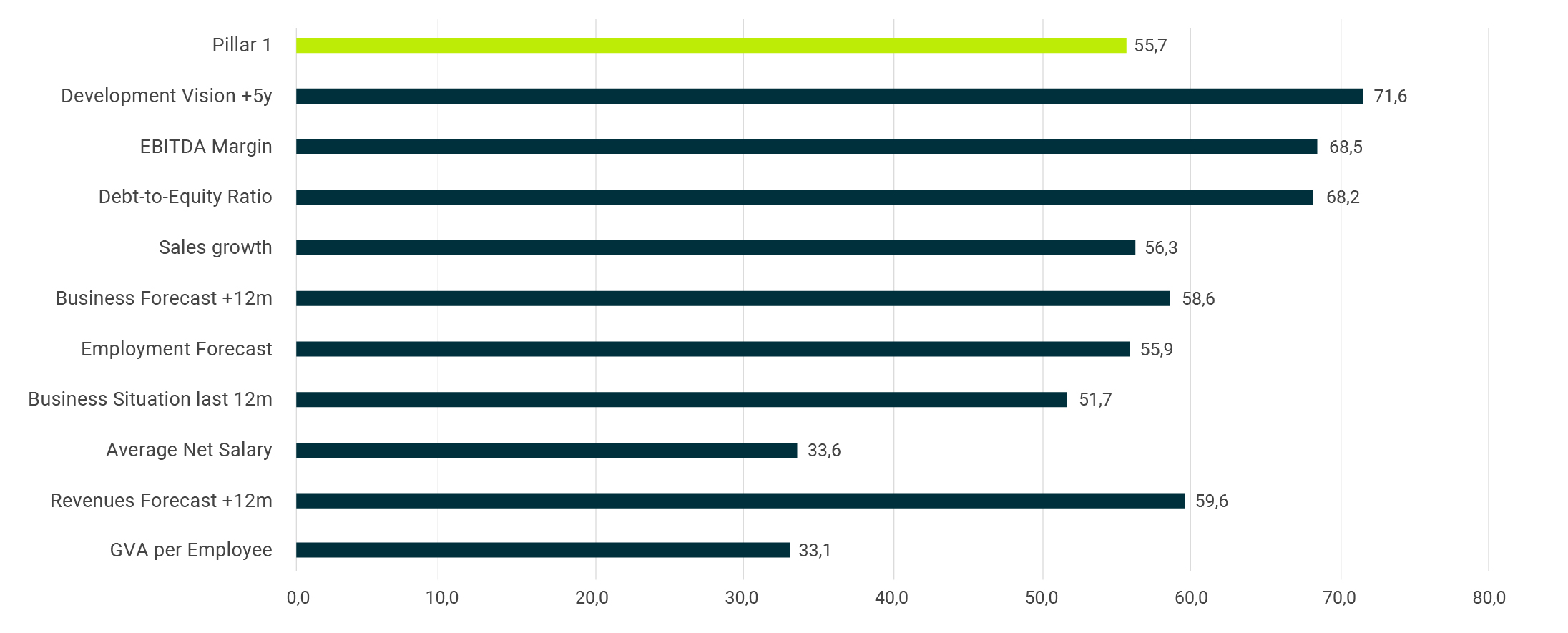

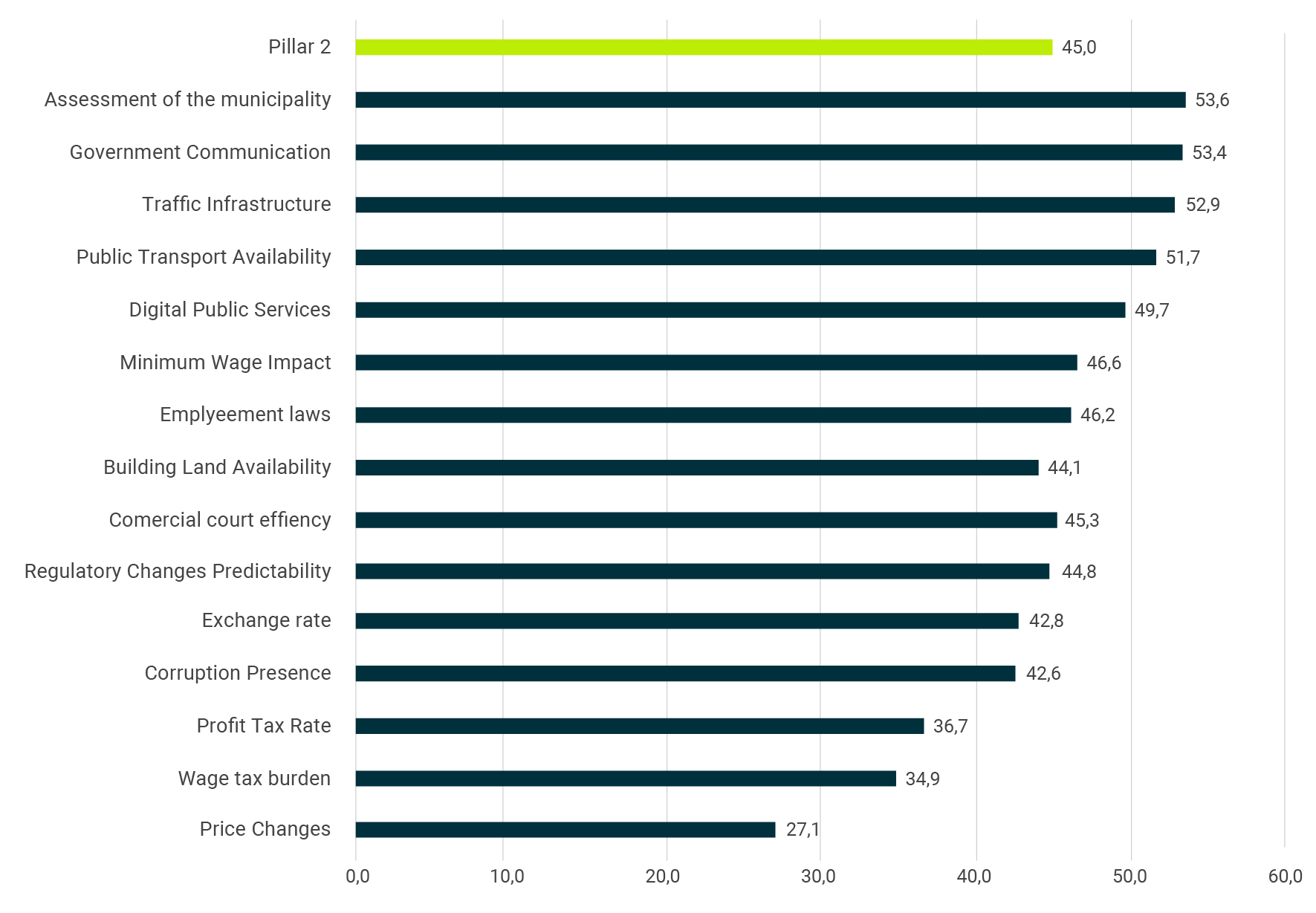

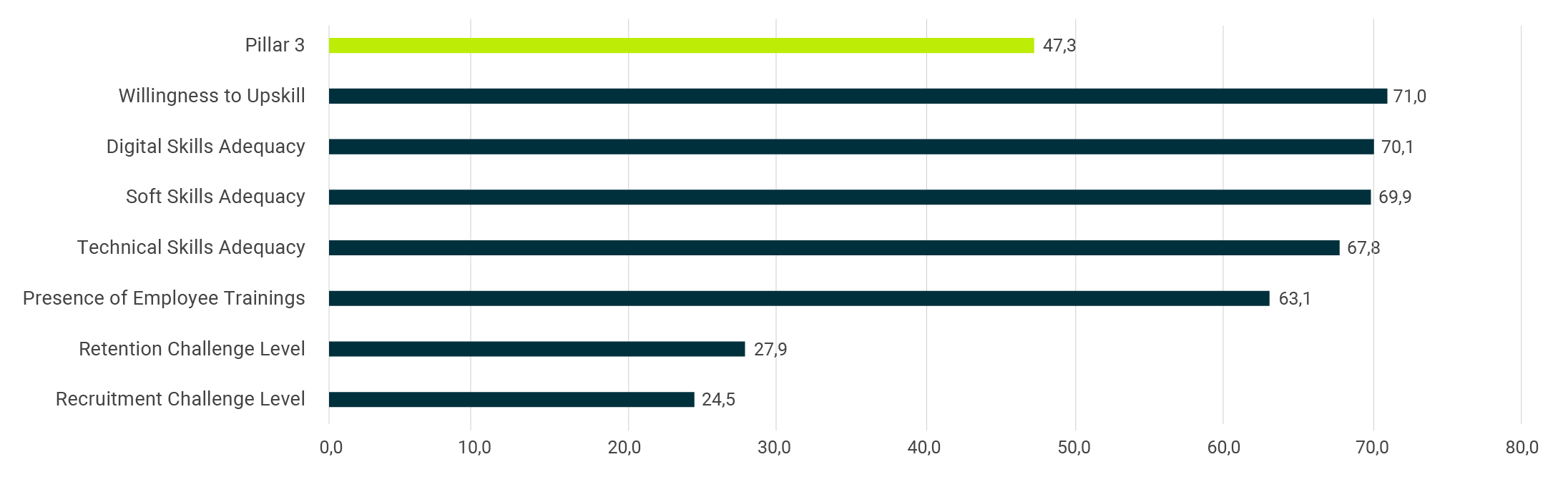

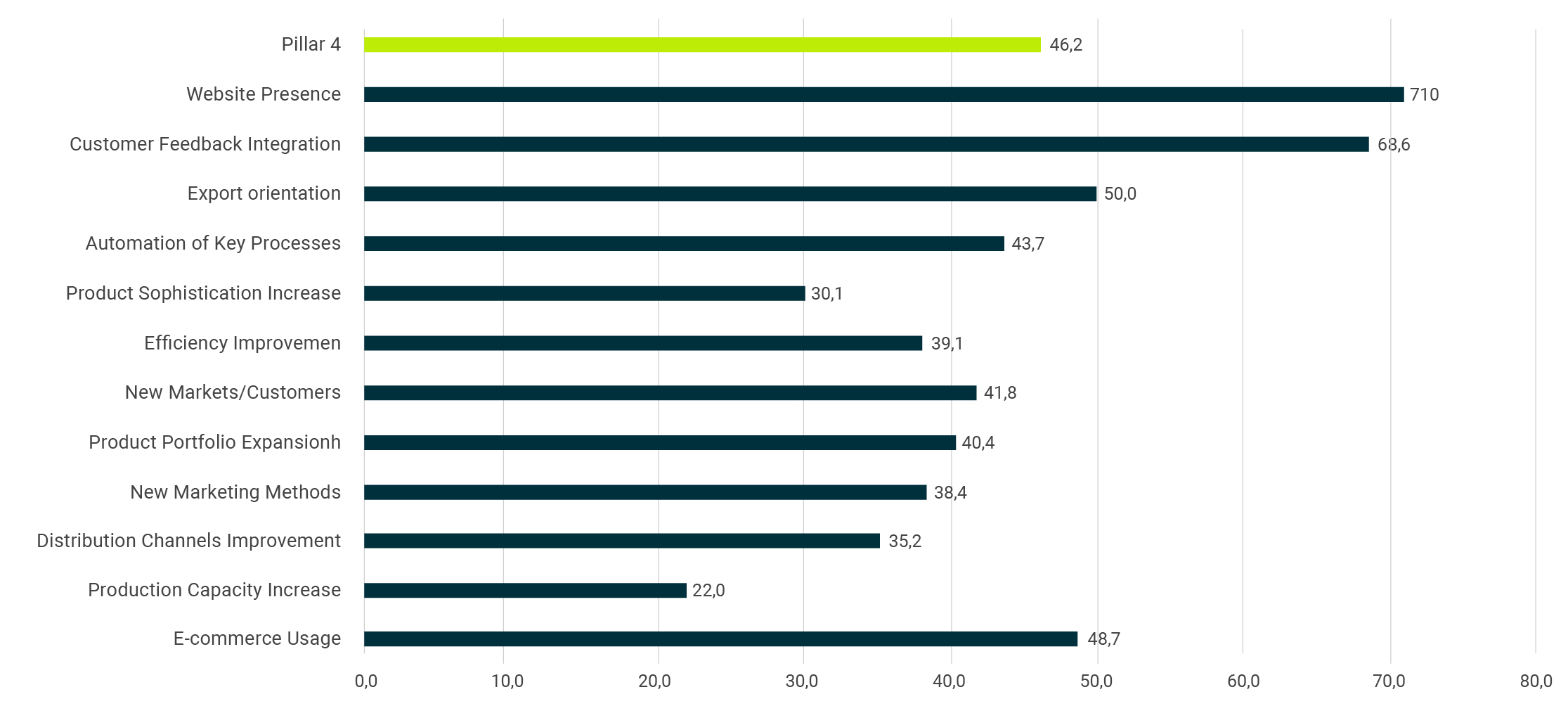

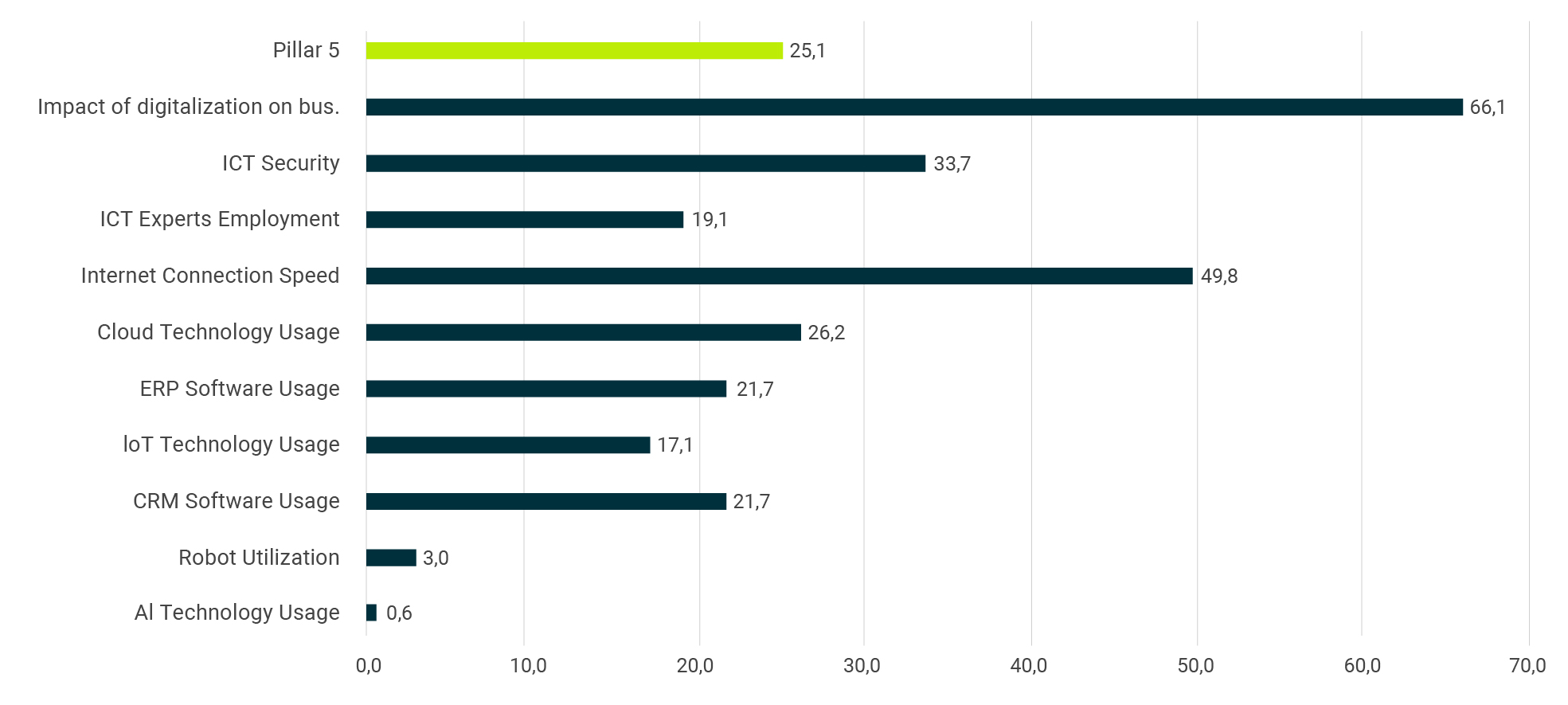

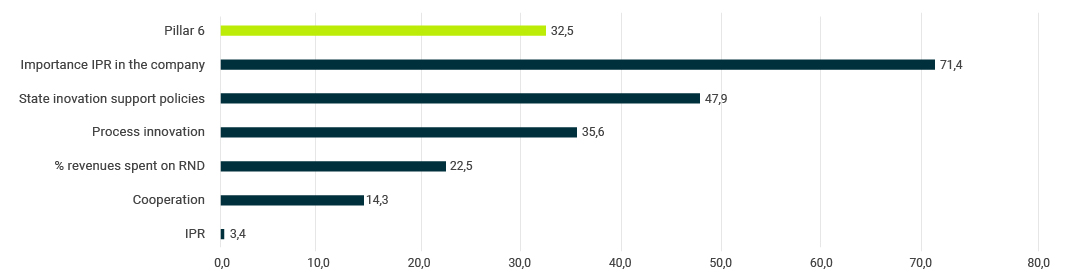

The CI for Serbia in 2023 stands at 40.1 out of 100, indicating a mid-low level of competitiveness and development in the private sector. Serbian SMEs excel in sentiment and performance, driven by overwhelmingly positive sentiments and long-term optimism. However, there are weaknesses in the areas of business model and human resources. Although workers in Serbia are praised for their quality, the labor shortage poses a significant constraint. While companies demonstrate export orientation, they make limited efforts to improve management and production, hindering innovation, green transformation, digitalization, and industry 4.0, resulting in poor CI scores in these areas.

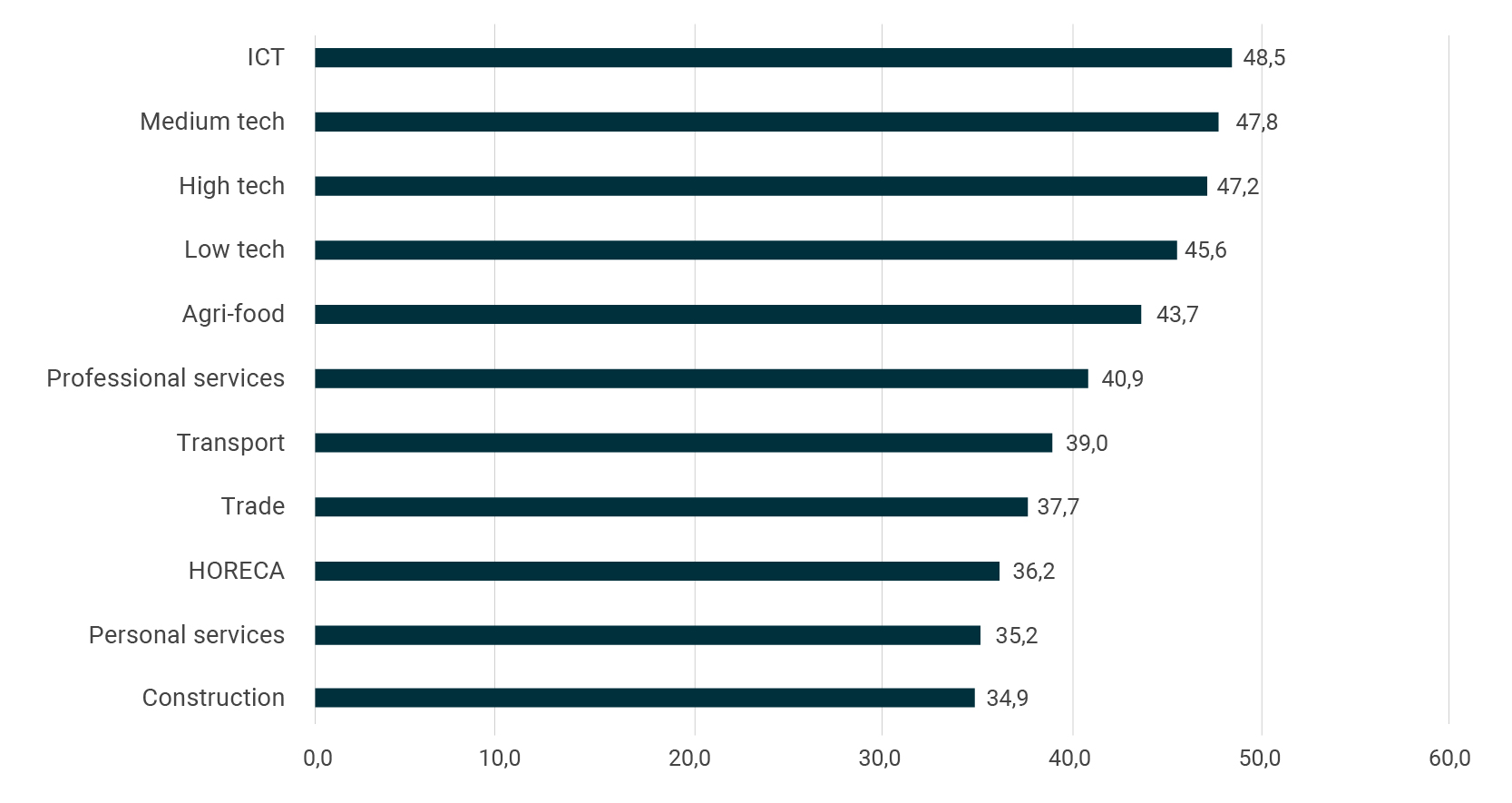

Among different sectors, higher value-added sectors outperform lower value-added ones. The top three most competitive sectors in Serbia are ICT, high-tech manufacturing, and mid-tech manufacturing. These sectors lead in economic performance, sentiment, business model development, and application of modern technologies and innovation. ICT and high-tech manufacturing are less constrained by the labor shortage and exhibit greater gender equity. Medium-tech manufacturing excels in business model development and green transformation. Sectors at the bottom face similar challenges but significantly lag behind in business model, digitalization, innovation, and green transformation.

Key takeaways from the CI analysis include:

- Positive economic sentiment is present in spite of global challenges.

- Companies hold a neutral or slightly negative attitude toward the business environment.

- The key structural problem lies in the labor shortage affecting all sectors and regions of Serbia.

- Serbia has a higher share of exporting companies compared to the EU, particularly in manufacturing. However, the average export intensity per company is weaker.

- Insufficient investments: Serbian SMEs lack adequate investment in equipment, processes, technologies, and expansion, also they collaborate less, altogether resulting in subpar digitalization, innovation and green transformation.

- Insufficient investments are not limited by the availability of external financing per se, as companies rarely use bank financing by choice.

- Gender equality: Women in the private sector face less favorable conditions, particularly in ownership, although their participation in employment and management positions is slightly better.